You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

On this day:

- Thread starter Singlemalt

- Start date

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"In the name of African-American voting rights, 3,200 civil rights demonstrators in Alabama, led by Martin Luther King Jr., begin a historic march from Selma to Montgomery on March 21, 1965, the state’s capital. Federalized Alabama National Guardsmen and FBI agents were on hand to provide safe passage for the march, which twice had been turned back by Alabama state police at Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In 1965, King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) decided to make the small town of Selma the focus of their drive to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Alabama’s governor, George Wallace, was a vocal opponent of the African-American civil rights movement, and local authorities in Selma had consistently thwarted efforts by the Dallas County Voters League and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to register local blacks.

Although Governor Wallace promised to prevent it from going forward, on March 7 some 500 demonstrators, led by SCLC leader Hosea Williams and SNCC leader John Lewis, began the 54-mile march to the state capital. After crossing Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were met by Alabama state troopers and posse men who attacked them with nightsticks, tear gas and whips after they refused to turn back.

Several of the protesters were severely beaten, and others ran for their lives. The incident was captured on national television and outraged many Americans.

King, who was in Atlanta at the time, promised to return to Selma immediately and lead another attempt. On March 9, King led another marching attempt, but turned the marchers around when state troopers again blocked the road.

On March 21, U.S. Army troops and federalized Alabama National Guardsmen escorted the marchers across Edmund Pettus Bridge and down Highway 80. When the highway narrowed to two lanes, only 300 marchers were permitted, but thousands more rejoined the Alabama Freedom March as it came into Montgomery on March 25.

On the steps of the Alabama State Capitol, King addressed live television cameras and a crowd of 25,000, just a few hundred feet from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where he got his start as a minister in 1954."

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

During a speech before the second Virginia Convention March 23, 1775, Patrick Henry responds to the increasingly oppressive British rule over the American colonies by declaring, “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Following the signing of the American Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, Patrick Henry was appointed governor of Virginia by the Continental Congress.

The first major American opposition to British policy came in 1765 after Parliament passed the Stamp Act, a taxation measure to raise revenues for a standing British army in America. Under the banner of “no taxation without representation,” colonists convened the Stamp Act Congress in October 1765 to vocalize their opposition to the tax. With its enactment on November 1, 1765, most colonists called for a boycott of British goods and some organized attacks on the customhouses and homes of tax collectors. After months of protest, Parliament voted to repeal the Stamp Act in March 1765.

Most colonists quietly accepted British rule until Parliament’s enactment of the Tea Act in 1773, which granted the East India Company a monopoly on the American tea trade. Viewed as another example of taxation without representation, militant Patriots in Massachusetts organized the “Boston Tea Party,” which saw British tea valued at some 10,000 pounds dumped into Boston harbor. Parliament, outraged by the Boston Tea Party and other blatant destruction of British property, enacted the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in the following year. The Coercive Acts closed Boston to merchant shipping, established formal British military rule in Massachusetts, made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in America, and required colonists to quarter British troops. The colonists subsequently called the first Continental Congress to consider a united American resistance to the British.

With the other colonies watching intently, Massachusetts led the resistance to the British, forming a shadow revolutionary government and establishing militias to resist the increasing British military presence across the colony. In April 1775, Thomas Gage, the British governor of Massachusetts, ordered British troops to march to Concord, Massachusetts, where a Patriot arsenal was known to be located. On April 19, 1775, the British regulars encountered a group of American militiamen at Lexington, and the first volleys of the American Revolutionary War were fired.

injinji

Well-Known Member

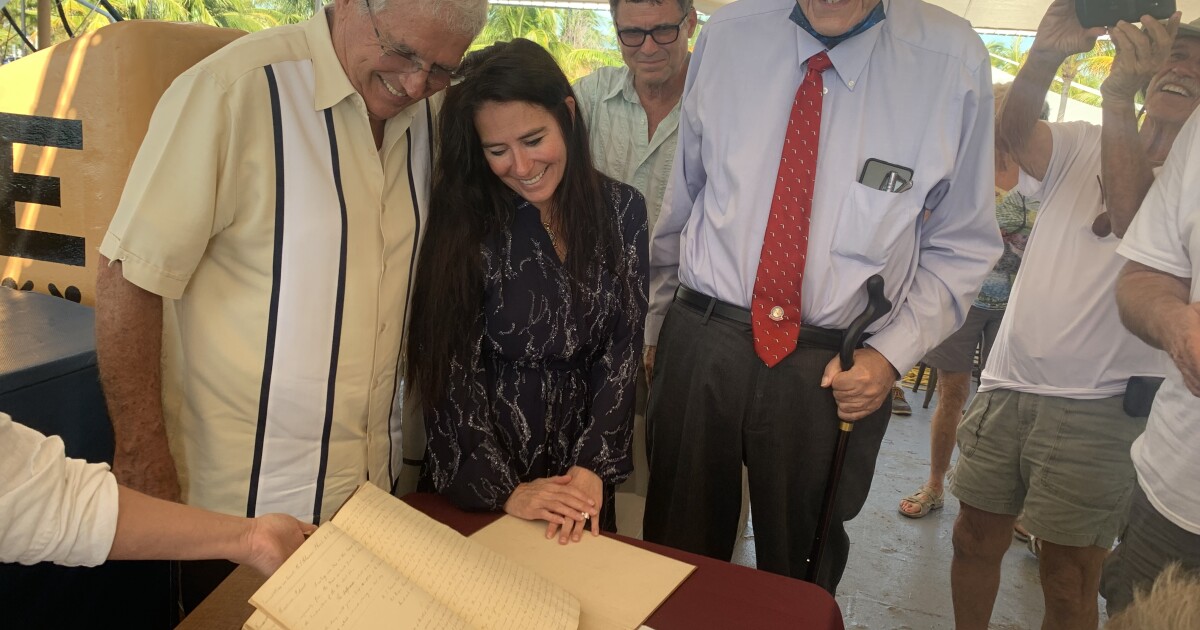

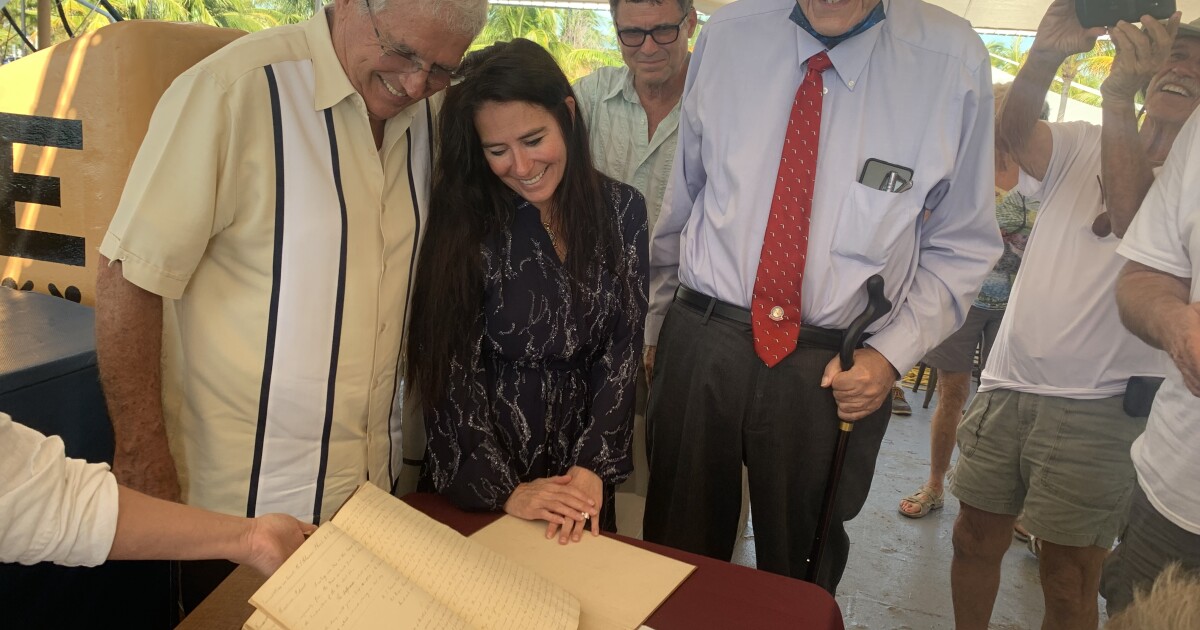

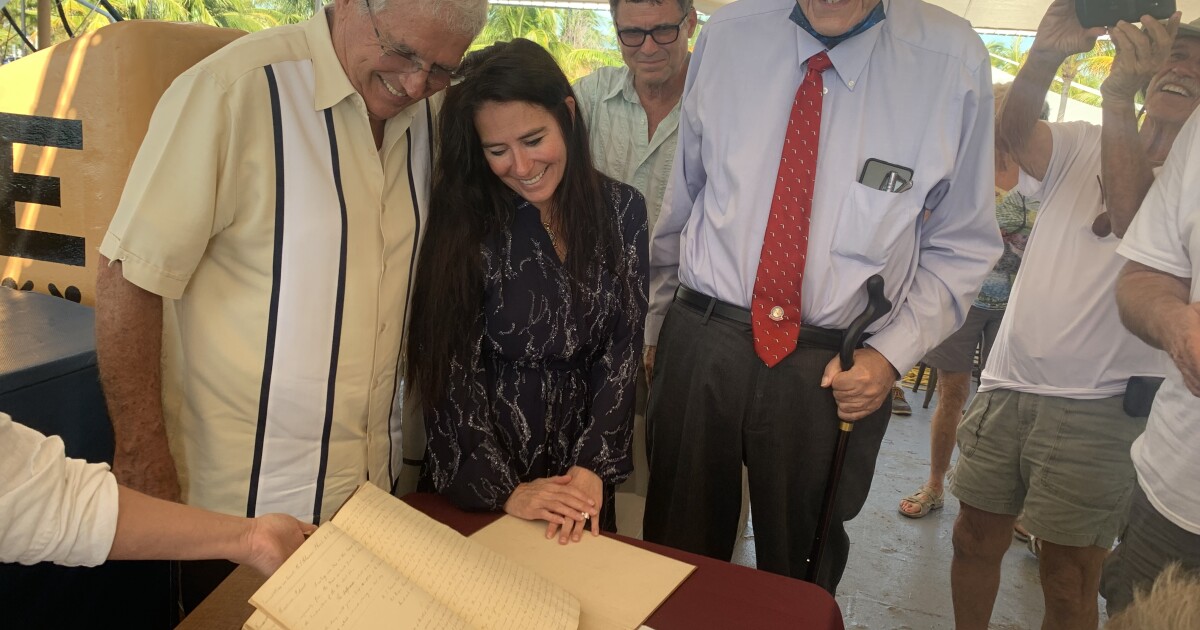

Two hundred years ago this week, the American flag was raised over the island of Key West for the first time.

The Navy sent the schooner Shark to check out Key West in 1822 after the island was bought by an American merchant.

Two hundred years later, the Shark's logbook is back in town. The Key West Maritime Historical Society recently acquired the journal and gave it to the Monroe County Library for its Florida History collection.

www.wlrn.org

www.wlrn.org

The Navy sent the schooner Shark to check out Key West in 1822 after the island was bought by an American merchant.

Two hundred years later, the Shark's logbook is back in town. The Key West Maritime Historical Society recently acquired the journal and gave it to the Monroe County Library for its Florida History collection.

Logbook documenting first official U.S. visit to Key West returns to the island after 200 years

The crew from the USS Shark raised the American flag over Key West for the first time on March 25, 1822. Now the ship's logbook is part of local historic archives.

injinji

Well-Known Member

Also 200 years ago this week, the first sighting of a land shark in Key West.Two hundred years ago this week, the American flag was raised over the island of Key West for the first time.

The Navy sent the schooner Shark to check out Key West in 1822 after the island was bought by an American merchant.

Two hundred years later, the Shark's logbook is back in town. The Key West Maritime Historical Society recently acquired the journal and gave it to the Monroe County Library for its Florida History collection.

Logbook documenting first official U.S. visit to Key West returns to the island after 200 years

The crew from the USS Shark raised the American flag over Key West for the first time on March 25, 1822. Now the ship's logbook is part of local historic archives.www.wlrn.org

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

March 24, 1989: One of the worst oil spills in U.S. history begins when the supertanker Exxon Valdez, owned and operated by the Exxon Corporation, runs aground on a reef in Prince William Sound in southern Alaska. An estimated 11 million gallons of oil eventually spilled into the water. Attempts to contain the massive spill were unsuccessful, and wind and currents spread the oil more than 100 miles from its source, eventually polluting more than 700 miles of coastline. Hundreds of thousands of birds and animals were adversely affected by the environmental disaster.

It was later revealed that Joseph Hazelwood, the captain of the Valdez, was drinking at the time of the accident and allowed an uncertified officer to steer the massive vessel. In March 1990, Hazelwood was convicted of misdemeanor negligence, fined $50,000, and ordered to perform 1,000 hours of community service. In July 1992, an Alaska court overturned Hazelwood’s conviction, citing a federal statute that grants freedom from prosecution to those who report an oil spill.

Exxon itself was condemned by the National Transportation Safety Board and in early 1991 agreed under pressure from environmental groups to pay a penalty of $100 million and provide $1 billion over a 10-year period for the cost of the cleanup. However, later in the year, both Alaska and Exxon rejected the agreement, and in October 1991 the oil giant settled the matter by paying $25 million, less than 4 percent of the cleanup aid promised by Exxon earlier that year.

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

On March 24, 2015, the co-pilot of a German airliner deliberately flies the plane into the French Alps, killing himself and the other 149 people onboard. When it crashed, Germanwings flight 9525 had been traveling from Barcelona, Spain, to Dusseldorf, Germany.

The plane took off from Barcelona around 10 a.m. local time and reached its cruising altitude of 38,000 feet at 10:27 a.m. Shortly afterward, the captain, 34-year-old Patrick Sondenheimer, requested that the co-pilot, 27-year-old Andreas Lubitz, take over the controls while he left the cockpit, probably to use the bathroom. At 10:31 a.m. the plane began a rapid descent and 10 minutes later crashed in mountainous terrain near the town of Prads-Haute-Bleone in southern France. There were no survivors. Besides the two pilots, the doomed Airbus A320 was carrying four cabin crew members and 144 passengers from 18 different countries, including three Americans.

Following the crash, investigators determined once the captain had stepped out of the cockpit Lubitz locked the door and wouldn’t let him back in. Sondenheimer could be heard on the plane’s black box voice recorder frantically yelling at his co-pilot and trying to break down the cockpit door. (In the aftermath of 9/11, Lufthansa installed fortified cockpit doors; however, when the Germanwings flight crashed the airline wasn’t required to have two crew members in the cockpit at all times, as U.S. carriers do.) Additionally, the flight data recorder showed Lubitz seemed to have rehearsed his suicide mission during an earlier flight that same day, when he repeatedly set the plane’s altitude dial to just 100 feet while the captain was briefly out of the cockpit. (Because Lubitz quickly reset the controls, his actions went unnoticed during the flight.)

Crash investigators also learned Lubitz had a history of severe depression and in the days before the disaster had searched the Internet for ways to die by suicide as well as for information about cockpit-door security. In 2008, Lubitz, a German native who flew gliders as a teen, entered the pilot-training program for Lufthansa, which owns budget-airliner Germanwings. He took time off from the program in 2009 to undergo treatment for psychological problems but later was readmitted and obtained his commercial pilot’s license in 2012. He started working for Germanwings in 2013. Investigators turned up evidence that in the months leading up to the crash Lubitz had visited a series of doctors for an unknown condition. He reportedly had notes declaring him unfit to work but kept this information from Lufthansa.

Instances of pilots using planes to die by suicide are rare. According to The New York Times, a U.S. Federal Aviation Administration study found that out of 2,758 aviation accidents documented by the FAA from 2003 to 2012, only eight were ruled suicides.

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"Each one came to America in the hope of a better life," said Annie Polland, a Senior Vice President at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. "Each one was probably supporting other family members. So the loss was almost, it was incalculable."

It's unclear exactly what started the fire, but it's believed that someone dropped a match or cigarette.

The door leading to the outside was locked -- some think the factory owner locked it to keep union organizers out. There was reportedly only one small working elevator, and no sprinkler system. The fire escape quickly broke under the weight of desperate workers trying to flee.

The women were trapped.

Firefighters arrived quickly on scene, but their ladders only reached the sixth floor, and their nets turned out to be too weak to catch women jumping from the windows.

Bystanders watched in horror as women leapt to their deaths, with very little they could do to help. The tragedy took a lasting toll on the city of New York -- and the public outcry led to government action to prevent another horrific inferno.

"This fire really shook people up," researcher Michael Hirsch told CBS News' Michelle Miller in 2011, the 100th anniversary of the fire.

"The city was so guilt-stricken. Everyone knew something was wrong, there was something wrong with that building and that maybe we were somehow responsible. And it led to all these reforms that came after."

The state of New York passed more than 36 new laws within a few years of the fire. The reforms included better fire and safety regulations as well as child labor laws -- since many of the Triangle workers were just teenagers.

One fire witness, Frances Perkins, went on to be Franklin D. Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor for 12 years. She became a champion for labor unions and worker rights, as well as minimum wage laws.

It's the kind of thing Hirsch told Miller in 2011 that he was committed to doing. He took it upon himself years ago to learn the stories of all 146 victims. He even connected with some of their family members -- often telling them for the first time they were related to someone who died in the fire.

It's important, he said, to remember who these people were and the lasting impact they had on the country.

"Their sacrifice, that terrible death, is the thing that really motivated people to start thinking about doing things differently in this country. So in a way, they are kind of heroes. I look at it that way."

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

On March 26, 1953, American medical researcher Dr. Jonas Salk announces on a national radio show that he has successfully tested a vaccine against poliomyelitis, the virus that causes the crippling disease of polio. In 1952—an epidemic year for polio—there were 58,000 new cases reported in the United States, and more than 3,000 died from the disease. For promising eventually to eradicate the disease, which is known as “infant paralysis” because it mainly affects children, Dr. Salk was celebrated as the great doctor-benefactor of his time.

Polio, a disease that has affected humanity throughout recorded history, attacks the nervous system and can cause varying degrees of paralysis. Since the virus is easily transmitted, epidemics were commonplace in the first decades of the 20th century. The first major polio epidemic in the United States occurred in Vermont in the summer of 1894, and by the 20th century thousands were affected every year. In the first decades of the 20th century, treatments were limited to quarantines and the infamous “iron lung,” a metal coffin-like contraption that aided respiration. Although children, and especially infants, were among the worst affected, adults were also often afflicted, including future president Franklin D. Roosevelt, who in 1921 was stricken with polio at the age of 39 and was left partially paralyzed. Roosevelt later transformed his estate in Warm Springs, Georgia, into a recovery retreat for polio victims and was instrumental in raising funds for polio-related research and the treatment of polio patients.

Salk, born in New York City in 1914, first conducted research on viruses in the 1930s when he was a medical student at New York University, and during World War II helped develop flu vaccines. In 1947, he became head of a research laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh and in 1948 was awarded a grant to study the polio virus and develop a possible vaccine. By 1950, he had an early version of his polio vaccine.

Salk’s procedure, first attempted unsuccessfully by American Maurice Brodie in the 1930s, was to kill several strains of the virus and then inject the benign viruses into a healthy person’s bloodstream. The person’s immune system would then create antibodies designed to resist future exposure to poliomyelitis. Salk conducted the first human trials on former polio patients and on himself and his family, and by 1953 was ready to announce his findings. This occurred on the CBS national radio network on the evening of March 25 and two days later in an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Dr. Salk became an immediate celebrity.

In 1954, clinical trials using the Salk vaccine and a placebo began on nearly two million American schoolchildren. In April 1955, it was announced that the vaccine was effective and safe, and a nationwide inoculation campaign began. Shortly thereafter, tragedy struck in the Western and mid-Western United States, when more than 200,000 people were injected with a defective vaccine manufactured at Cutter Laboratories of Berkeley, California. Thousands of polio cases were reported, 200 children were left paralyzed and 10 died.

The incident delayed production of the vaccine, but new polio cases dropped to under 6,000 in 1957, the first year after the vaccine was widely available. In 1962, an oral vaccine developed by Polish-American researcher Albert Sabin became available, greatly facilitating distribution of the polio vaccine. Today, there are just a handful of polio cases in the United States every year. Among other honors, Jonas Salk was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977. He died in La Jolla, California, in 1995

DarkWeb

Well-Known Member

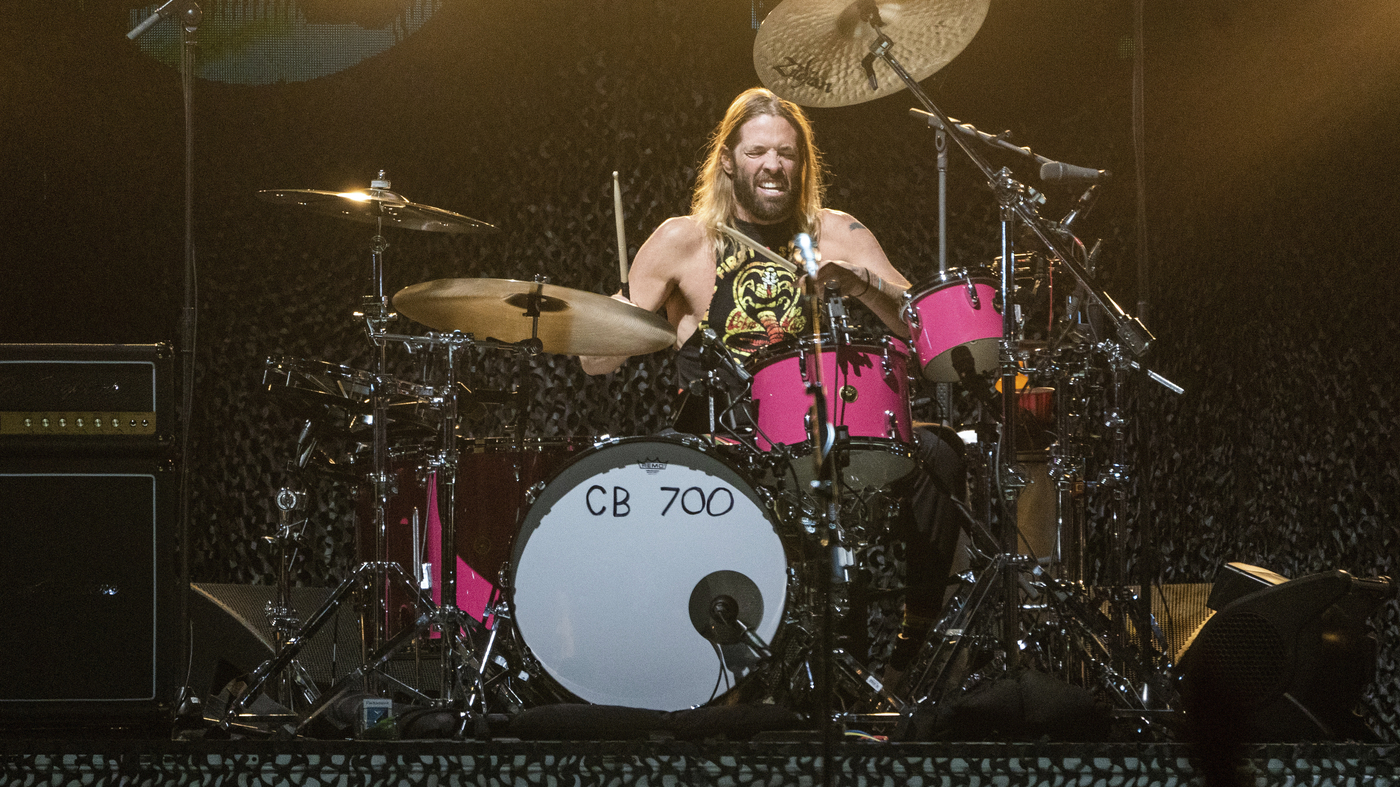

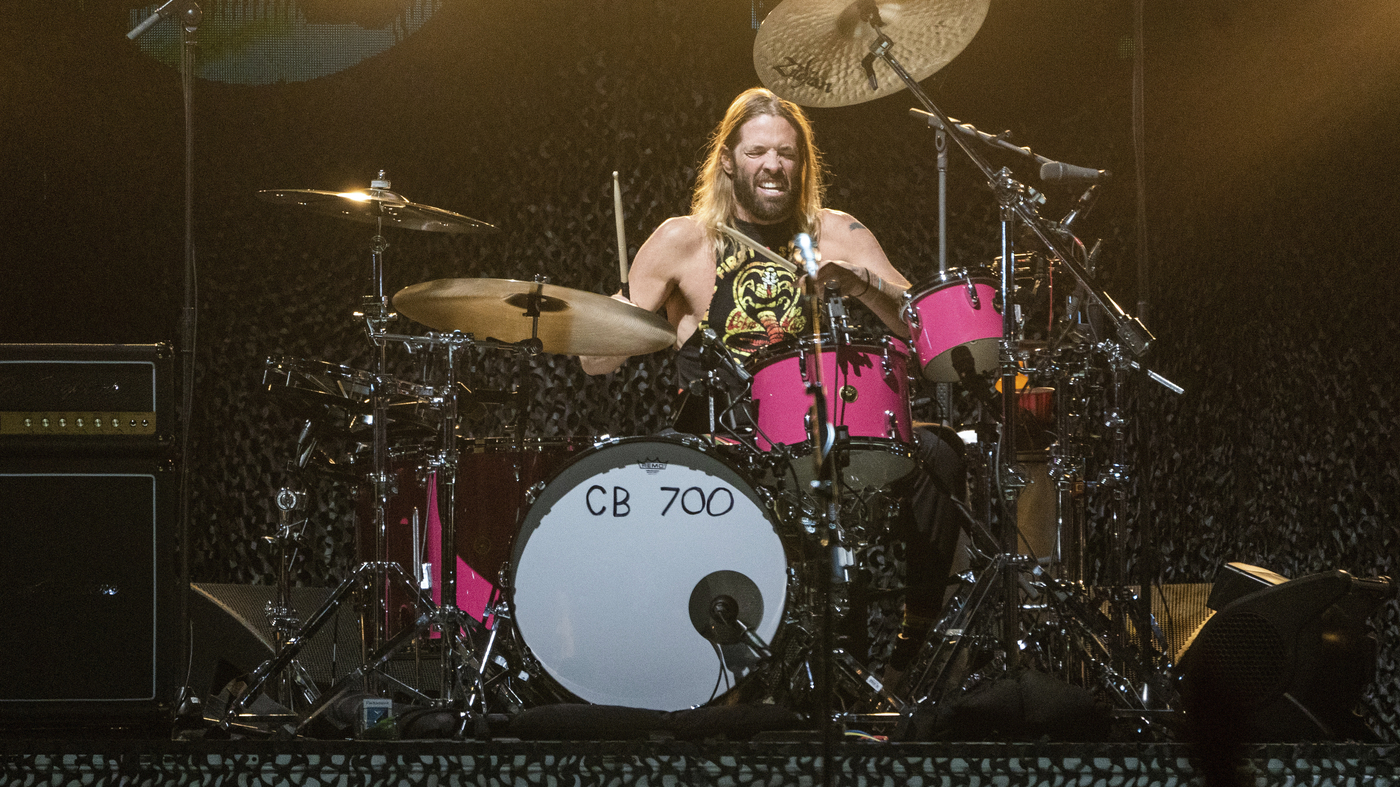

RIP Taylor

www.npr.org

www.npr.org

Foo Fighters drummer Taylor Hawkins dies at 50

The longtime drummer for the megaplatinum band has died. On Saturday, Colombian officials released a statement, saying they found evidence of 10 types of substances in Hawkins' body.

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

On March 27, 1964, the strongest earthquake in American history, measuring 9.2 on the Richter scale, slams southern Alaska, creating a deadly tsunami. Some 131 people were killed and thousands injured.

The massive earthquake had its epicenter about 12 miles north of Prince William Sound. Approximately 300,000 square miles of U.S., Canadian, and international territory were affected. Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, sustained the most property damage, with about 30 blocks of dwellings and commercial buildings damaged or destroyed in the downtown area. Fifteen people were killed or fatally injured as a direct result of the three-minute quake, and then the ensuing tsunami killed another 110 people.

The tidal wave, which measured over 100 feet at points, devastated towns along the Gulf of Alaska and caused carnage in British Columbia, Canada; Hawaii; and the West Coast of the United States, where 15 people died. Total property damage was estimated in excess of $400 million. The day after the quake, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared Alaska an official disaster area.

Last edited:

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

On March 27, 1977, two 747 jumbo jets crash into each other on the runway at an airport in the Canary Islands, killing 583 passengers and crew members. It remains the deadliest accident in the history of aviation.

Both Boeing 747s were charter jets that were not supposed to be at the Los Rodeos Airport on Santa Cruz de Tenerife that day. Both had been scheduled to be at the Las Palmas Airport, where a group of militants had set off a small bomb at the airport’s flower shop earlier that day. Thus, a Pan Am charter carrying passengers from Los Angeles and New York to a Mediterranean cruise and a KLM charter with Dutch tourists were both diverted to Santa Cruz on March 27.

The Los Rodeos airport is known for its sudden fog problems and was not a favorite location for pilots. At 4:40 p.m. on a typically foggy afternoon, the KLM jet was cleared to taxi to the end of the single main runway. The Pan Am jet followed behind it and was to wait in side space while the KLM jet turned around to begin takeoff. However, in the fog, the Pan Am pilot was unable to keep the KLM jet in sight and did not move into the proper position. The Dutch crew of the KLM jet, apparently unable to understand the accented English spoken by the flight controllers, began to take off down the runway before the Pan Am jet was able to move to the side space.

At the last minute, the Pan Am pilot saw the other 747 coming straight at his own jet and screamed, "What’s he doing? He’ll kill us all!" while attempting to swerve into a grassy field. It was too late. The KLM 747 slammed into the side of the Pan Am jet and both planes erupted into a huge fireball. The only survivors on either plane were those in the very front of the Pan Am 747.

Dorothy Kelly – The Tenerife Air Disaster.

March 27, 1977 is a date permanently etched in aviation history. 583 lives were lost when a KLM 747 collided with a Pan Am 747 at Tenerife’s Los Rodeos Airport (TFN). It remains the worlds deadlies…

AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT TENERIFE, CANARY ISLANDS MARCH 27, 1977

Ironically it happened on Good Friday.

On March 27, 1964, the strongest earthquake in American history, measuring 9.2 on the Richter scale, slams southern Alaska, creating a deadly tsunami. Some 131 people were killed and thousands injured.

The massive earthquake had its epicenter about 12 miles north of Prince William Sound. Approximately 300,000 square miles of U.S., Canadian, and international territory were affected. Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, sustained the most property damage, with about 30 blocks of dwellings and commercial buildings damaged or destroyed in the downtown area. Fifteen people were killed or fatally injured as a direct result of the three-minute quake, and then the ensuing tsunami killed another 110 people.

The tidal wave, which measured over 100 feet at points, devastated towns along the Gulf of Alaska and caused carnage in British Columbia, Canada; Hawaii; and the West Coast of the United States, where 15 people died. Total property damage was estimated in excess of $400 million. The day after the quake, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared Alaska an official disaster area.

2nd pic looks like downtown Kodiak.

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"At 4 a.m. on March 28, 1979, the worst accident in the history of the U.S. nuclear power industry begins when a pressure valve in the Unit-2 reactor at Three Mile Island fails to close. Cooling water, contaminated with radiation, drained from the open valve into adjoining buildings, and the core began to dangerously overheat.

The Three Mile Island nuclear power plant was built in 1974 on a sandbar on Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna River, just 10 miles downstream from the state capitol in Harrisburg. In 1978, a second state-of-the-art reactor began operating on Three Mile Island, which was lauded for generating affordable and reliable energy in a time of energy crises.

After the cooling water began to drain out of the broken pressure valve on the morning of March 28, 1979, emergency cooling pumps automatically went into operation. Left alone, these safety devices would have prevented the development of a larger crisis. However, human operators in the control room misread confusing and contradictory readings and shut off the emergency water system. The reactor was also shut down, but residual heat from the fission process was still being released. By early morning, the core had heated to over 4,000 degrees, just 1,000 degrees short of meltdown. In the meltdown scenario, the core melts, and deadly radiation drifts across the countryside, fatally sickening a potentially great number of people.

As the plant operators struggled to understand what had happened, the contaminated water was releasing radioactive gases throughout the plant. The radiation levels, though not immediately life-threatening, were dangerous, and the core cooked further as the contaminated water was contained and precautions were taken to protect the operators. Shortly after 8 a.m., word of the accident leaked to the outside world. The plant’s parent company, Metropolitan Edison, downplayed the crisis and claimed that no radiation had been detected off plant grounds, but the same day inspectors detected slightly increased levels of radiation nearby as a result of the contaminated water leak. Pennsylvania Governor Dick Thornburgh considered calling an evacuation.

Finally, at about 8 p.m., plant operators realized they needed to get water moving through the core again and restarted the pumps. The temperature began to drop, and pressure in the reactor was reduced. The reactor had come within less than an hour of a complete meltdown. More than half the core was destroyed or molten, but it had not broken its protective shell, and no radiation was escaping. The crisis was apparently over.

Two days later, however, on March 30, a bubble of highly flammable hydrogen gas was discovered within the reactor building. The bubble of gas was created two days before when exposed core materials reacted with super-heated steam. On March 28, some of this gas had exploded, releasing a small amount of radiation into the atmosphere. At that time, plant operators had not registered the explosion, which sounded like a ventilation door closing. After the radiation leak was discovered on March 30, residents were advised to stay indoors. Experts were uncertain if the hydrogen bubble would create further meltdown or possibly a giant explosion, and as a precaution Governor Thornburgh advised “pregnant women and pre-school age children to leave the area within a five-mile radius of the Three Mile Island facility until further notice.” This led to the panic the governor had hoped to avoid; within days, more than 100,000 people had fled surrounding towns.

On April 1, President Jimmy Carter arrived at Three Mile Island to inspect the plant. Carter, a trained nuclear engineer, had helped dismantle a damaged Canadian nuclear reactor while serving in the U.S. Navy. His visit achieved its aim of calming local residents and the nation. That afternoon, experts agreed that the hydrogen bubble was not in danger of exploding. Slowly, the hydrogen was bled from the system as the reactor cooled.

At the height of the crisis, plant workers were exposed to unhealthy levels of radiation, but no one outside Three Mile Island had their health adversely affected by the accident. Nonetheless, the incident greatly eroded the public’s faith in nuclear power. The unharmed Unit-1 reactor at Three Mile Island, which was shut down during the crisis, did not resume operation until 1985. Cleanup continued on Unit-2 until 1990, but it was too damaged to be rendered usable again. In the four decades since the accident at Three Mile Island, not a single new nuclear power plant has been ordered in the United States."

Three Mile Island | TMI 2 |Three Mile Island Accident. - World Nuclear Association

Three Mile Island: In 1979 at Three Mile Island in USA a cooling malfunction caused part of the (TMI 2) core to melt. The reactor was destroyed but there were no injuries or adverse health effects from the Three Mile Island accident. Some radioactive gas was released a couple of days after the...

Last edited:

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"March 29, 1973: Two months after the signing of the Vietnam peace agreement, the last U.S. combat troops leave South Vietnam as Hanoi frees the remaining American prisoners of war held in North Vietnam. America’s direct eight-year intervention in the Vietnam War was at an end. In Saigon, some 7,000 U.S. Department of Defense civilian employees remained behind to aid South Vietnam in conducting what looked to be a fierce and ongoing war with communist North Vietnam.

In 1961, after two decades of indirect military aid, U.S. President John F. Kennedy sent the first large force of U.S. military personnel to Vietnam to bolster the ineffectual autocratic regime of South Vietnam against the communist North. Three years later, with the South Vietnamese government crumbling, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered limited bombing raids on North Vietnam, and Congress authorized the use of U.S. troops. By 1965, North Vietnamese offensives left President Johnson with two choices: escalate U.S. involvement or withdraw. Johnson ordered the former, and troop levels soon jumped to more than 300,000 as U.S. air forces commenced the largest bombing campaign in history.

During the next few years, the extended length of the war, the high number of U.S. casualties, and the exposure of U.S. involvement in war crimes, such as the massacre at My Lai, helped turn many in the United States against the Vietnam War. The communists’ Tet Offensive of 1968 crushed U.S. hopes of an imminent end to the conflict and galvanized U.S. opposition to the war. In response, Johnson announced in March 1968 that he would not seek reelection, citing what he perceived to be his responsibility in creating a perilous national division over Vietnam. He also authorized the beginning of peace talks.

In the spring of 1969, as protests against the war escalated in the United States, U.S. troop strength in the war-torn country reached its peak at nearly 550,000 men. Richard Nixon, the new U.S. president, began U.S. troop withdrawal and “Vietnamization” of the war effort that year, but he intensified bombing. Large U.S. troop withdrawals continued in the early 1970s as President Nixon expanded air and ground operations into Cambodia and Laos in attempts to block enemy supply routes along Vietnam’s borders. This expansion of the war, which accomplished few positive results, led to new waves of protests in the United States and elsewhere.

Finally, in January 1973, representatives of the United States, North and South Vietnam, and the Vietcong signed a peace agreement in Paris, ending the direct U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam War. Its key provisions included a cease-fire throughout Vietnam, the withdrawal of U.S. forces, the release of prisoners of war, and the reunification of North and South Vietnam through peaceful means. The South Vietnamese government was to remain in place until new elections were held, and North Vietnamese forces in the South were not to advance further nor be reinforced.

In reality, however, the agreement was little more than a face-saving gesture by the U.S. government. Even before the last American troops departed on March 29, the communists violated the cease-fire, and by early 1974 full-scale war had resumed. At the end of 1974, South Vietnamese authorities reported that 80,000 of their soldiers and civilians had been killed in fighting during the year, making it the most costly of the Vietnam War.

On April 30, 1975, the last few Americans still in South Vietnam were airlifted out of the country as Saigon fell to communist forces. North Vietnamese Colonel Bui Tin, accepting the surrender of South Vietnam later in the day, remarked, “You have nothing to fear; between Vietnamese there are no victors and no vanquished. Only the Americans have been defeated.” The Vietnam War was the longest and most unpopular foreign war in U.S. history and cost 58,000 American lives. As many as two million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians were killed."

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"On March 30, 1981, President Ronald Reagan is shot in the chest outside a Washington, D.C. hotel by a drifter named John Hinckley Jr.

The president had just finished addressing a labor meeting at the Washington Hilton Hotel and was walking with his entourage to his limousine when Hinckley, standing among a group of reporters, fired six shots at the president, hitting Reagan and three of his attendants. White House Press Secretary James Brady was shot in the head and critically wounded, Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy was shot in the side, and District of Columbia policeman Thomas Delahanty was shot in the neck. After firing the shots, Hinckley was overpowered and pinned against a wall, and President Reagan, apparently unaware that he’d been shot, was shoved into his limousine by a Secret Service agent and rushed to the hospital.

The president was shot in the left lung, and the .22 caliber bullet just missed his heart. In an impressive feat for a 70-year-old man with a collapsed lung, he walked into George Washington University Hospital under his own power. As he was treated and prepared for surgery, he was in good spirits and quipped to his wife, Nancy, ”Honey, I forgot to duck,” and to his surgeons, “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” Reagan’s surgery lasted two hours, and he was listed in stable and good condition afterward.

The next day, the president resumed some of his executive duties and signed a piece of legislation from his hospital bed. On April 11, he returned to the White House. Reagan’s popularity soared after the assassination attempt, and at the end of April he was given a hero’s welcome by Congress. In August, this same Congress passed his controversial economic program, with several Democrats breaking ranks to back Reagan’s plan. By this time, Reagan claimed to be fully recovered from the assassination attempt. In private, however, he would continue to feel the effects of the nearly fatal gunshot wound for years.

Of the victims of the assassination attempt, Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy and D.C. policeman Thomas Delahanty eventually recovered. James Brady, who nearly died after being shot in the eye, suffered permanent brain damage. He later became an advocate of gun control, and in 1993 Congress passed the “Brady Bill,” which established a five-day waiting period and background checks for prospective gun buyers. President Bill Clinton signed the bill into law.

After being arrested on March 30, 1981, 25-year-old John Hinckley was booked on federal charges of attempting to assassinate the president. He had previously been arrested in Tennessee on weapons charges. In June 1982, he was found not guilty by reason of insanity. In the trial, Hinckley’s defense attorneys argued that their client was ill with narcissistic personality disorder, citing medical evidence, and had a pathological obsession with the 1976 film Taxi Driver, in which the main character attempts to assassinate a fictional senator.

His lawyers claimed that Hinckley saw the movie more than a dozen times, was obsessed with the lead actress, Jodie Foster, and had attempted to reenact the events of the film in his own life. Thus the movie, not Hinckley, they argued, was the actual planning force behind the events that occurred on March 30, 1981.

The verdict of “not guilty by reason of insanity” aroused widespread public criticism, and many were shocked that a would-be presidential assassin could avoid been held accountable for his crime. However, because of his obvious threat to society, he was placed in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, a mental institution. In the late 1990s, Hinckley’s attorney began arguing that his mental illness was in remission and thus had a right to return to a normal life.

Beginning in August 1999, he was allowed supervised day trips off the hospital grounds and later was allowed to visit his parents once a week unsupervised. The Secret Service voluntarily monitored him during these outings.

On July 27, 2016, a federal judge ruled that Hinckley could be released from St. Elizabeths on August 5, as he was no longer considered a threat to himself or others. Hinckley was released from institutional psychiatric care on September 10, 2016, with many conditions. He was required to live full-time at his mother's home in Williamsburg. In addition, the following prohibitions and requirements were imposed on him

On November 16, 2018, Judge Friedman ruled Hinckley could move out of his mother's house in Virginia and live on his own upon location approval from his doctors. On September 10, 2019, Hinckley's attorney stated that he had planned to ask for full, unconditional release from the court orders that determined how he could live by the end of that year. On September 27, 2021, a federal judge approved Hinckley for unconditional release beginning June 2022.

Brady died on August 4, 2014, in Alexandria, Virginia. Four days later, the medical examiner ruled that his death was a homicide, caused by the gunshot wound which he sustained in 1981. Hinckley did not face any charges for Brady's death because he had been found not guilty by reason of insanity.

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"On April 1, 1945, after suffering the loss of 116 planes and damage to three aircraft carriers, 50,000 U.S. combat troops, under the command of Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner Jr., land on the southwest coast of the Japanese island of Okinawa, 350 miles south of Kyushu, the southern main island of Japan.

Determined to seize Okinawa as a base of operations for the army ground and air forces for a later assault on mainland Japan, more than 1,300 ships converged on the island, finally putting ashore 50,000 combat troops on April 1. The Americans quickly seized two airfields and advanced inland to cut the island’s waist. They battled nearly 120,000 Japanese army, militia and labor troops under the command of Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima.

The Japanese surprised the American forces with a change in strategy, drawing them into the mainland rather than confronting them at the water’s edge. While Americans landed without loss of men, they would suffer more than 50,000 casualties, including more than 12,000 deaths, as the Japanese staged a desperate defense of the island, a defense that included waves of kamikaze (“divine wind”) air attacks. Eventually, these suicide raids proved counterproductive, as the Japanese finally ran out of planes and resolve, with some 4,000 finally surrendering. Japanese casualties numbered some 117,000.

Lieutenant General Buckner, son of a Civil War general, was among the casualties, killed by enemy artillery fire just three days before the Japanese surrender. Japanese General Ushijima committed ritual suicide upon defeat of his forces.

On an individual basis, 24 service members received the Medal of Honor for actions performed during the Battle of Okinawa. Thirteen went to the Marines and their organic Navy corpsmen, nine to Army troops, and one to a Navy officer. 28 Navy Crosses were also awarded.

The Secretary of the Navy awarded Presidential Unit Citations to the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing, and Marine Observation Squadron Three (VMO-3) for "extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese forces during the invasion of Okinawa." Marine Observation Squadron Six also received the award as a specified attached unit to the 6th Marine Division.

Many of those Marines who survived Okinawa went on to positions of top leadership that influenced the Corps for the next two decades or more. Two Commandants emerged — General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., of the 6th Marine Division, and then-Lieutenant Colonel Leonard F. Chapman, Jr., CO of 4/11. Oliver P. Smith and Vernon E. Megee rose to four-star rank. At least 17 others achieved the rank of lieutenant general, including George C. Axtell, Jr.; Victor H. Krulak; Alan Shapley; and Edward W. Snedeker. And Corporal James L. Day recovered from his wounds and returned to Okinawa 40 years later as a major general to command all Marine Corps bases on the island.

www.britannica.com

www.britannica.com

Determined to seize Okinawa as a base of operations for the army ground and air forces for a later assault on mainland Japan, more than 1,300 ships converged on the island, finally putting ashore 50,000 combat troops on April 1. The Americans quickly seized two airfields and advanced inland to cut the island’s waist. They battled nearly 120,000 Japanese army, militia and labor troops under the command of Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima.

The Japanese surprised the American forces with a change in strategy, drawing them into the mainland rather than confronting them at the water’s edge. While Americans landed without loss of men, they would suffer more than 50,000 casualties, including more than 12,000 deaths, as the Japanese staged a desperate defense of the island, a defense that included waves of kamikaze (“divine wind”) air attacks. Eventually, these suicide raids proved counterproductive, as the Japanese finally ran out of planes and resolve, with some 4,000 finally surrendering. Japanese casualties numbered some 117,000.

Lieutenant General Buckner, son of a Civil War general, was among the casualties, killed by enemy artillery fire just three days before the Japanese surrender. Japanese General Ushijima committed ritual suicide upon defeat of his forces.

On an individual basis, 24 service members received the Medal of Honor for actions performed during the Battle of Okinawa. Thirteen went to the Marines and their organic Navy corpsmen, nine to Army troops, and one to a Navy officer. 28 Navy Crosses were also awarded.

The Secretary of the Navy awarded Presidential Unit Citations to the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, the 2d Marine Aircraft Wing, and Marine Observation Squadron Three (VMO-3) for "extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese forces during the invasion of Okinawa." Marine Observation Squadron Six also received the award as a specified attached unit to the 6th Marine Division.

Many of those Marines who survived Okinawa went on to positions of top leadership that influenced the Corps for the next two decades or more. Two Commandants emerged — General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., of the 6th Marine Division, and then-Lieutenant Colonel Leonard F. Chapman, Jr., CO of 4/11. Oliver P. Smith and Vernon E. Megee rose to four-star rank. At least 17 others achieved the rank of lieutenant general, including George C. Axtell, Jr.; Victor H. Krulak; Alan Shapley; and Edward W. Snedeker. And Corporal James L. Day recovered from his wounds and returned to Okinawa 40 years later as a major general to command all Marine Corps bases on the island.

Battle of Okinawa - Intensified, Collapsed, Resistance | Britannica

Battle of Okinawa - Intensified, Collapsed, Resistance: The elements of the 10th Army that had moved south toward the main population centres of Naha and Shuri encountered the fiercest kind of resistance. As on Iwo Jima, the Japanese fought with great tenacity and succeeded in making the...

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"Joel, this is Marty. I'm calling you from a cell phone, a real handheld portable cell phone."

--Motorola engineer Marty Cooper to Joel Engel, a rival from the research department at Bell Labs, April 3, 1973

Motorola’s Marty Cooper made the first call from a handheld mobile phone (distinct from car phones) to Joel S. Engel, a rival at Bell Labs, on April 3, 1973. Bell Labs had envisioned such technology as early as the late 1940s and, by Cooper’s own admission, he couldn’t help but playfully rub the monumental moment in a bit.

Cooper made the call during an interview with reporters located near a 900-MHz base station on 6th Avenue, between 53rd and 54th Streets in New York, to Bell Labs’ New Jersey headquarters.

The call was made on a prototype of the DynaTAC (dynamic adaptive total area coverage) 8000X, which, 10 years later, would become the first such phone to be commercially released. In 1973, it weighed 1.1 kg and measured 22.86 cm long, 12.7 cm deep, and 4.44 cm wide. The prototype offered a talk time of about 20 minutes and took 10 hours to recharge. Cooper was not concerned about the limited talk time as it would be difficult to hold something of that weight and size to an ear for more than 20 minutes.

Cooper, an engineer and executive at Motorola at the time, played an important role in the development of mobile phones. His belief was that a cellular phone should be “something that would represent an individual so you could assign a number — not to a place, not to a desk, not to a home — but to a person.”

Motorola management was supportive of Cooper’s mobile phone concept and invested $100 million between 1973 and 1993 before any revenues were realized. Forty years to the day after this call was made, Cooper was named the 2013 Marconi Prize recipient on April 3, 2013.

Marty Cooper Found His Calling: The Cellphone

Exclusive interview with investor who changed the world.

BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

"Just after 6 p.m. on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. is fatally shot while standing on the balcony outside his second-story room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. The civil rights leader was in Memphis to support a sanitation workers’ strike and was on his way to dinner when a bullet struck him in the jaw and severed his spinal cord. King was pronounced dead after his arrival at a Memphis hospital. He was 39 years old.

In the months before his assassination, Martin Luther King became increasingly concerned with the problem of economic inequality in America. He organized a Poor People’s Campaign to focus on the issue, including a march on Washington, and in March 1968 traveled to Memphis in support of poorly treated African-American sanitation workers. On March 28, a workers’ protest march led by King ended in violence and the death of an African American teenager. King left the city but vowed to return in early April to lead another demonstration.

On April 3, back in Memphis, King gave his last sermon, saying, “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop … And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.”

One day after speaking those words, Dr. King was shot and killed by a sniper. As word of the assassination spread, riots broke out in cities all across the United States and National Guard troops were deployed in Memphis and Washington, D.C. On April 9, King was laid to rest in his hometown of Atlanta, Georgia. Tens of thousands of people lined the streets to pay tribute to King’s casket as it passed by in a wooden farm cart drawn by two mules.

The evening of King’s murder, a Remington .30-06 hunting rifle was found on the sidewalk beside a rooming house one block from the Lorraine Motel. During the next several weeks, the rifle, eyewitness reports, and fingerprints on the weapon all implicated a single suspect: escaped convict James Earl Ray. A two-bit criminal, Ray escaped a Missouri prison in April 1967 while serving a sentence for a holdup. In May 1968, a massive manhunt for Ray began. The FBI eventually determined that he had obtained a Canadian passport under a false identity, which at the time was relatively easy.

On June 8, Scotland Yard investigators arrested Ray at a London airport. He was trying to fly to Belgium, with the eventual goal, he later admitted, of reaching Rhodesia. Rhodesia, now called Zimbabwe, was at the time ruled by an oppressive and internationally condemned white minority government. Extradited to the United States, Ray stood before a Memphis judge in March 1969 and pleaded guilty to King’s murder in order to avoid the electric chair. He was sentenced to 99 years in prison.

Three days later, he attempted to withdraw his guilty plea, claiming he was innocent of King’s assassination and had been set up as a patsy in a larger conspiracy. He claimed that in 1967, a mysterious man named “Raoul” had approached him and recruited him into a gunrunning enterprise. On April 4, 1968, he said, he realized that he was to be the fall guy for the King assassination and fled to Canada. Ray’s motion was denied, as were his dozens of other requests for a trial during the next 29 years.

During the 1990s, the widow and children of Martin Luther King Jr. spoke publicly in support of Ray and his claims, calling him innocent and speculating about an assassination conspiracy involving the U.S. government and military. U.S. authorities were, in conspiracists’ minds, implicated circumstantially. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover obsessed over King, who he thought was under communist influence. For the last six years of his life, King underwent constant wiretapping and harassment by the FBI. Before his death, Dr. King was also monitored by U.S. military intelligence, which may have been asked to watch King after he publicly denounced the Vietnam War in 1967. Furthermore, by calling for radical economic reforms in 1968, including guaranteed annual incomes for all, King was making few new friends in the Cold War-era U.S. government.

Over the years, the assassination has been reexamined by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, the Shelby County, Tennessee, district attorney’s office, and three times by the U.S. Justice Department. The investigations all ended with the same conclusion: James Earl Ray killed Martin Luther King. The House committee acknowledged that a low-level conspiracy might have existed, involving one or more accomplices to Ray, but uncovered no evidence to definitively prove this theory. In addition to the mountain of evidence against him–such as his fingerprints on the murder weapon and his admitted presence at the rooming house on April 4–Ray had a definite motive in assassinating King: hatred. According to his family and friends, he was an outspoken racist who informed them of his intent to kill Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He died in 1998."

In the months before his assassination, Martin Luther King became increasingly concerned with the problem of economic inequality in America. He organized a Poor People’s Campaign to focus on the issue, including a march on Washington, and in March 1968 traveled to Memphis in support of poorly treated African-American sanitation workers. On March 28, a workers’ protest march led by King ended in violence and the death of an African American teenager. King left the city but vowed to return in early April to lead another demonstration.

On April 3, back in Memphis, King gave his last sermon, saying, “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop … And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the promised land.”

One day after speaking those words, Dr. King was shot and killed by a sniper. As word of the assassination spread, riots broke out in cities all across the United States and National Guard troops were deployed in Memphis and Washington, D.C. On April 9, King was laid to rest in his hometown of Atlanta, Georgia. Tens of thousands of people lined the streets to pay tribute to King’s casket as it passed by in a wooden farm cart drawn by two mules.

The evening of King’s murder, a Remington .30-06 hunting rifle was found on the sidewalk beside a rooming house one block from the Lorraine Motel. During the next several weeks, the rifle, eyewitness reports, and fingerprints on the weapon all implicated a single suspect: escaped convict James Earl Ray. A two-bit criminal, Ray escaped a Missouri prison in April 1967 while serving a sentence for a holdup. In May 1968, a massive manhunt for Ray began. The FBI eventually determined that he had obtained a Canadian passport under a false identity, which at the time was relatively easy.

On June 8, Scotland Yard investigators arrested Ray at a London airport. He was trying to fly to Belgium, with the eventual goal, he later admitted, of reaching Rhodesia. Rhodesia, now called Zimbabwe, was at the time ruled by an oppressive and internationally condemned white minority government. Extradited to the United States, Ray stood before a Memphis judge in March 1969 and pleaded guilty to King’s murder in order to avoid the electric chair. He was sentenced to 99 years in prison.

Three days later, he attempted to withdraw his guilty plea, claiming he was innocent of King’s assassination and had been set up as a patsy in a larger conspiracy. He claimed that in 1967, a mysterious man named “Raoul” had approached him and recruited him into a gunrunning enterprise. On April 4, 1968, he said, he realized that he was to be the fall guy for the King assassination and fled to Canada. Ray’s motion was denied, as were his dozens of other requests for a trial during the next 29 years.

During the 1990s, the widow and children of Martin Luther King Jr. spoke publicly in support of Ray and his claims, calling him innocent and speculating about an assassination conspiracy involving the U.S. government and military. U.S. authorities were, in conspiracists’ minds, implicated circumstantially. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover obsessed over King, who he thought was under communist influence. For the last six years of his life, King underwent constant wiretapping and harassment by the FBI. Before his death, Dr. King was also monitored by U.S. military intelligence, which may have been asked to watch King after he publicly denounced the Vietnam War in 1967. Furthermore, by calling for radical economic reforms in 1968, including guaranteed annual incomes for all, King was making few new friends in the Cold War-era U.S. government.

Over the years, the assassination has been reexamined by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, the Shelby County, Tennessee, district attorney’s office, and three times by the U.S. Justice Department. The investigations all ended with the same conclusion: James Earl Ray killed Martin Luther King. The House committee acknowledged that a low-level conspiracy might have existed, involving one or more accomplices to Ray, but uncovered no evidence to definitively prove this theory. In addition to the mountain of evidence against him–such as his fingerprints on the murder weapon and his admitted presence at the rooming house on April 4–Ray had a definite motive in assassinating King: hatred. According to his family and friends, he was an outspoken racist who informed them of his intent to kill Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He died in 1998."

Similar threads

- Replies

- 105

- Views

- 11K

- Replies

- 324

- Views

- 23K