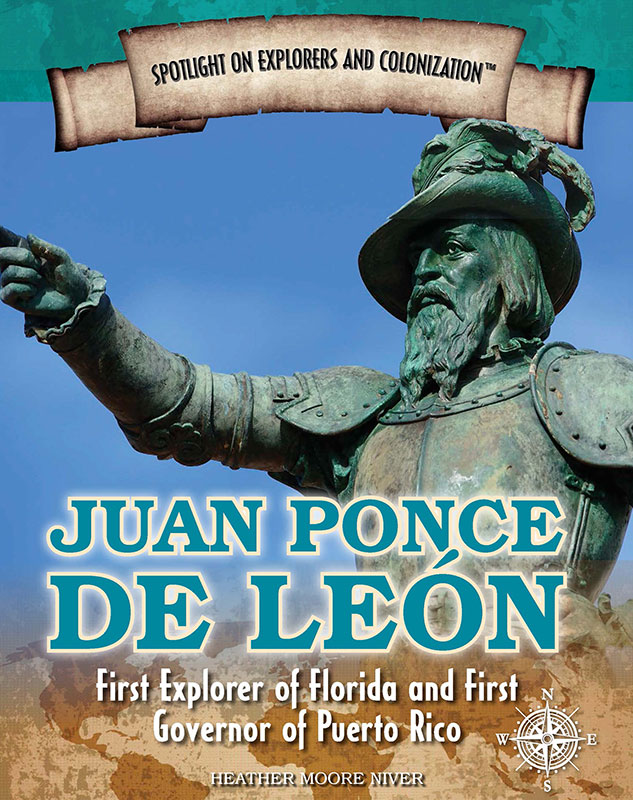

Written records about life in Florida began with the arrival of the Spanish explorer and adventurer Juan Ponce de León in 1513. Sometime between April 2 and April 8, Ponce de León waded ashore on the northeast coast of Florida, possibly near present-day St. Augustine. He called the area la Florida, in honor of Pascua florida ("feast of the flowers"), Spain's Eastertime celebration. Other Europeans may have reached Florida earlier, but no firm evidence of such achievement has been found.

On another voyage in 1521, Ponce de León landed on the southwestern coast of the peninsula, accompanied by two-hundred people, fifty horses, and numerous beasts of burden. His colonization attempt quickly failed because of attacks by native people. However, Ponce de León's activities served to identify Florida as a desirable place for explorers, missionaries, and treasure seekers.

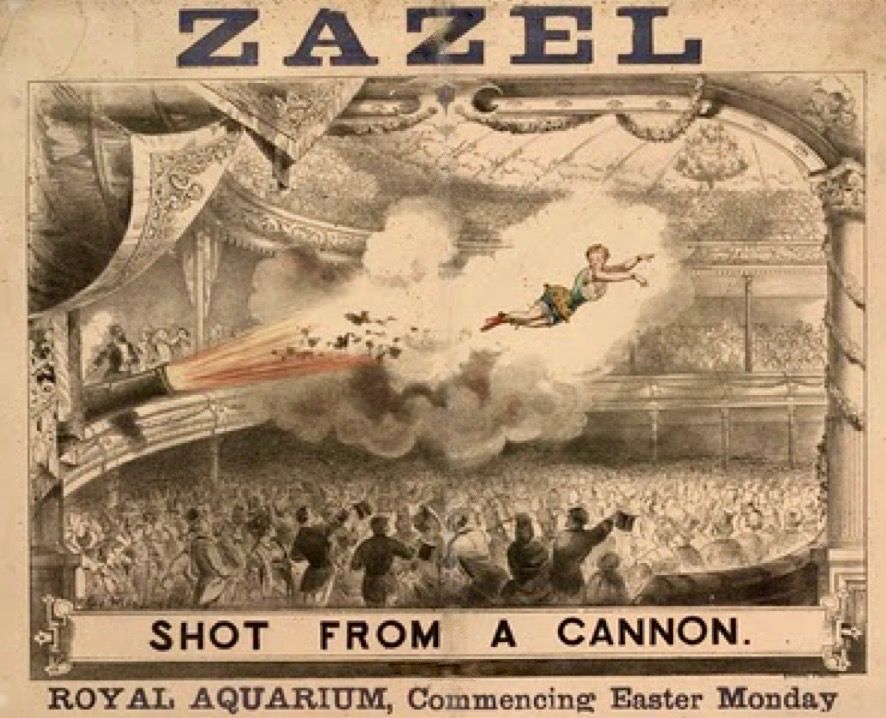

"Zazel" makes her spectacular entrance over an astonished crowd

by Ray Setterfield

April 2, 1877 — First there was an explosion, then a puff of smoke, and then, on this day, the first human cannonball was propelled into the air about 60 feet above the heads of an astonished crowd.

She was Rosa Matilda Richter, a 14-year-old English girl who performed under the decidedly un-English name of “Zazel”. A tightrope walker and aerial acrobat, Rosa had learnt her craft from William Hunt, a Canadian who gloried under the title of The Great Farini. He was most famous for performing a high-wire walk above Niagara Falls.

In 1871 he patented the mechanism for launching a human projectile through the air into a safety net. Fortunately for Rosa, the process did not actually involve any explosive, her ejection from the “cannon” being achieved by a system of springs and tension, accompanied by a fake explosion and smoke.

Still, the London spectators who witnessed the first performance in 1877 were wildly impressed and excited. It happened at the Royal Aquarium, a place of entertainment that had been built next to Westminster Abbey the previous year and which continued to pull in crowds until it was demolished in 1903.

Despite her physical prowess and acrobatic ability, the act was not without danger for Rosa. The springs-and-tension method of propulsion – replaced in modern times by compressed air – was hardly precise and the day came, almost inevitably, when she shot through the air and missed the safety net.

Fortunate to survive, Zazel, the human cannonball, who had been playing to crowds of 20,000 in England and the United States, broke her back and was forced to retire.