injinji

Well-Known Member

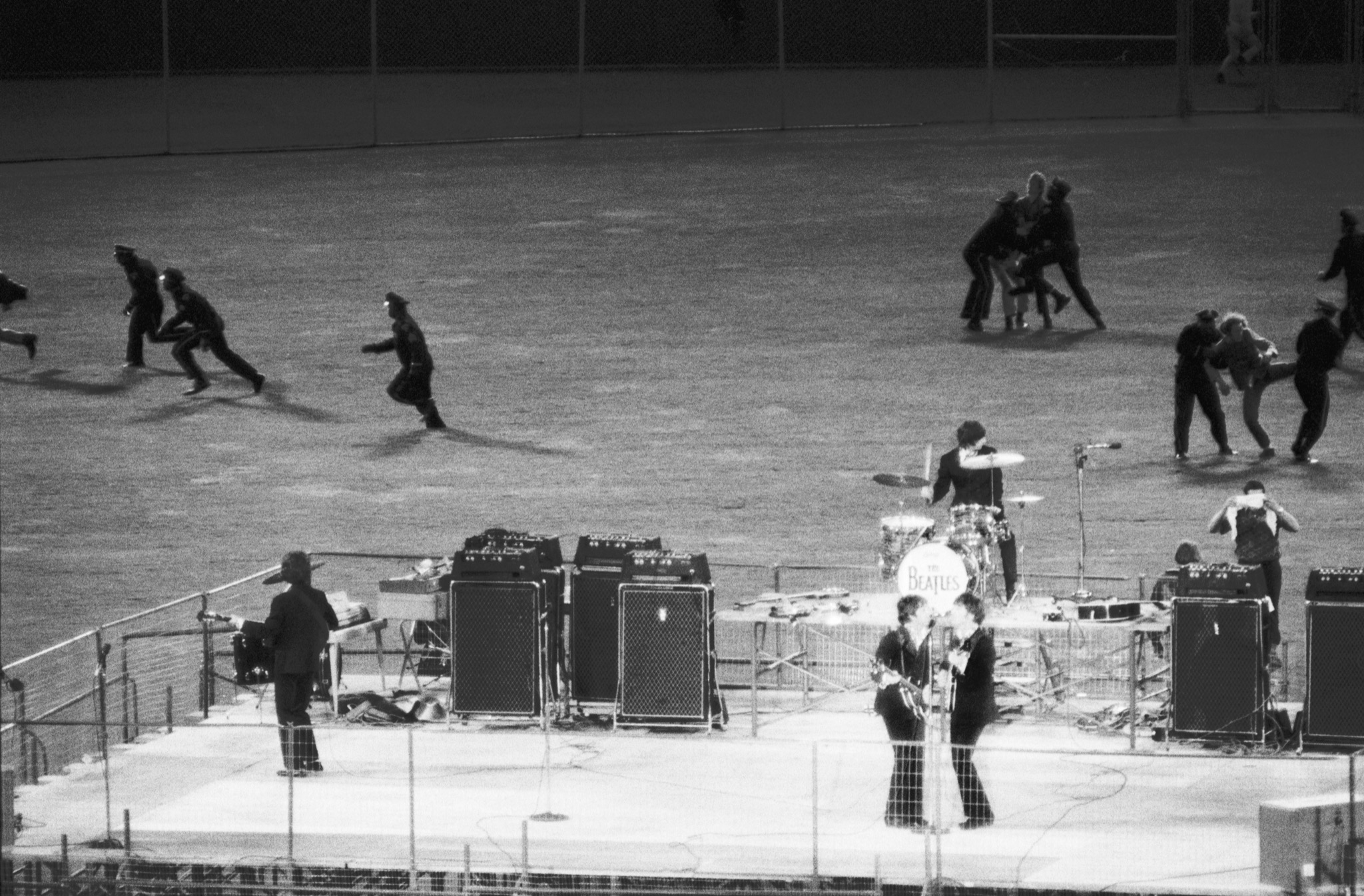

The story of the Beatles' last official concert, which took place in San Francisco

55 years ago today, the Fab Four played Candlestick Park

The story of the Beatles' last official concert, which took place in SF

At the time, almost no one knew Candlestick Park would be their last stadium show.www.sfgate.com