BarnBuster

Virtually Unknown Member

Today in Military History:

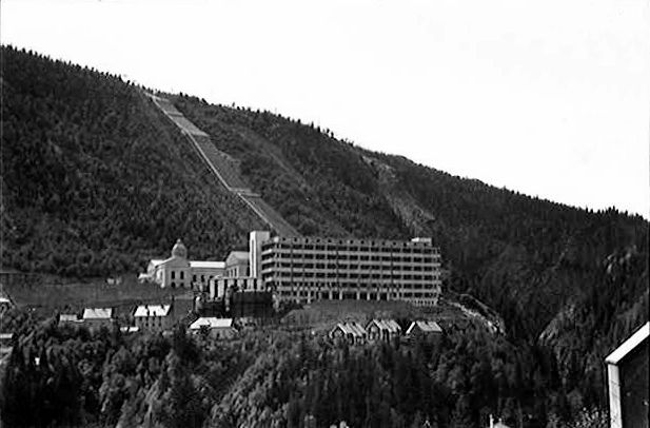

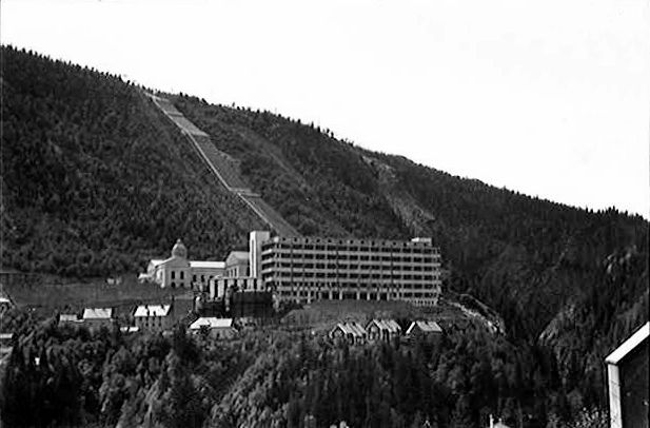

At 8:00 p.m. on February 27, 1943, nine Norwegian commandos trained by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) left their hideout in the Norwegian wilderness and skied several miles to Norsk Hydro's Vemork hydroelectric power plant. All the men knew about their mission was the objective: Destroy Vemork's "heavy water" production capabilities.

The operation was a resounding success. The commandos destroyed the electrolysis cells and over 500 kg of heavy water. They managed to escape without firing a single shot or taking any casualties.

The Germans repaired the damage by May, but subsequent Allied air raids prevented full-scale production. Eventually, the Germans ceased all production of heavy water and tried to move the remaining supply to Germany.

In a last act of sabotage, a Norwegian team led by one of the Gunnerside commandos sank the ferry transporting the remaining heavy water on February 20, 1944, although at the cost of 14 Norwegian civilians.

The operations helped foil Germany's nuclear ambitions, and the Nazis never built an atomic bomb or a nuclear reactor. Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies in early May 1945, two months before the US's bigger and better-resourced Manhattan Project tested the first nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945.

Their mission would be one of the most successful in special-operations history, and it contributed to one of the Allies' most important goals in World War II: Preventing Nazi Germany from developing nuclear weapons.

All members of the team were decorated, with Joachim Rønneberg, the mission commander receiving Britain's DSO and Norway's War Cross with Sword' the highest ranking Norwegian gallantry decoration. Media coverage of the Vemork missions (a total of six) was extensive. In addition to books and articles, in 1948 a Norwegian movie about the missions was released, starring some members of the team. In 1965, Columbia Pictures released the movie The Heroes of Telemark starring Kirk Douglas and Richard Harris, a highly fictionalized version of the action.

www.businessinsider.com

www.businessinsider.com

military-history.fandom.com

military-history.fandom.com

www.tracesofwar.com

www.tracesofwar.com

At 8:00 p.m. on February 27, 1943, nine Norwegian commandos trained by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) left their hideout in the Norwegian wilderness and skied several miles to Norsk Hydro's Vemork hydroelectric power plant. All the men knew about their mission was the objective: Destroy Vemork's "heavy water" production capabilities.

The operation was a resounding success. The commandos destroyed the electrolysis cells and over 500 kg of heavy water. They managed to escape without firing a single shot or taking any casualties.

The Germans repaired the damage by May, but subsequent Allied air raids prevented full-scale production. Eventually, the Germans ceased all production of heavy water and tried to move the remaining supply to Germany.

In a last act of sabotage, a Norwegian team led by one of the Gunnerside commandos sank the ferry transporting the remaining heavy water on February 20, 1944, although at the cost of 14 Norwegian civilians.

The operations helped foil Germany's nuclear ambitions, and the Nazis never built an atomic bomb or a nuclear reactor. Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies in early May 1945, two months before the US's bigger and better-resourced Manhattan Project tested the first nuclear weapon on July 16, 1945.

Their mission would be one of the most successful in special-operations history, and it contributed to one of the Allies' most important goals in World War II: Preventing Nazi Germany from developing nuclear weapons.

All members of the team were decorated, with Joachim Rønneberg, the mission commander receiving Britain's DSO and Norway's War Cross with Sword' the highest ranking Norwegian gallantry decoration. Media coverage of the Vemork missions (a total of six) was extensive. In addition to books and articles, in 1948 a Norwegian movie about the missions was released, starring some members of the team. In 1965, Columbia Pictures released the movie The Heroes of Telemark starring Kirk Douglas and Richard Harris, a highly fictionalized version of the action.

How a daring raid by Norwegian commandos kept the Nazis from building a nuclear bomb

The Norwegian commandos who set out on Operation Gunnerside knew what their objective was but not what was at stake.

Norwegian heavy water sabotage

The Norwegian heavy water sabotage was a series of actions undertaken by Norwegian salboteurs during World War II to prevent the German nuclear energy project from acquiring heavy water (deuterium oxide), which could be used to produce nuclear weapons. In 1934, at Vemork, Norsk Hydro built the...